[extract of Les Indomptables, MSc thesis]

During the fieldwork experience, I met farmers who -partly- disagree with modernization discourse, had different projects, and who were looking for something else. Thus, they frame modern changes as -source of- problems and they formulate critiques that call for stepping out of these processes and rethinking their logic of farming. They have their own categories to talk about these connected problems; the four next sub-sections gather thoughts, stories, standpoints, and worldviews that show both threat and critical thinking and that call for creativity.

Industry? We don’t fit!

Farmers I met consider their relations with upstream and downstream industries as problematic on different aspects. First, industries prevent them from “décider nous-mêmes” (lit. deciding on our own). Some farmers told me stories about other farmers who adopted innovations (farm systems) offered by industries and that reduced their room for manoeuvre. « Ils se mettent dans des systèmes impossibles » (lit. they put themselves in complicated systems) for instance they install automatic calf feeders but they have to buy milk powder, they grow commercial crops (potatoes and vegetables for can industry) but they must « tout acheter » (lit. buy everything) for cattle. Another farmer told me that dairy industries make new kinds of contracts with farmers in Germany. The dairy “dicte comment il faut faire” (lit. lays down how to do), “dicte le prix” (lays down the price), “ils ont investi, ils sont coincés” (the farmers have invested, they are stuck). In the same vein, farmers are fed up with vendors that try to convince them to invest in larger buildings, machines, tractors than what they actually want. The vendors « embobine le fermier dans la folie des grandeurs » (lit. enrolls the farmer in delusions of grandeur), then “le fermier a du mal” (the farmer has difficulties). « Les marchands nous manipulent, l’agriculture n’est qu’un prétexte pour le business. On la fait vivre pour ça » (lit. salesmen manipulate us; agriculture is just a pretext for doing business. They make it live just for that reason). Farmers formulate vendors’ offers as dangerous traps or risky options. « Quand est-ce qu’ils vont comprendre? » (when will the farmers understand ?) ; « il ne faut jamais faire confiance à tous ces représentants » (one should never trust in all these vendors).

Secondly, they consider that industries make them work in ways they don’t want to. Farmers disagree with the normative framework of industrial technologies and farm systems. Farmers I met position themselves in opposition to industrial farming i.e. farming along the lines of industrial codes and prescriptions. For instance, a farmer told me that his neighbor, industrial pig farmer, had a problem with the ventilation system during few hours. The next day, sixty tons of dead pigs were lying in the courtyard; “ce n’est pas un problème” (lit. it is not a problem [for those farmers]), the insurance intervened. On the opposite, I have been told many times “nous, on n’aime pas les robots” (lit. we don’t like milking robots); « je respecte mes vaches » (I do respect my cattle), “je ne supporte pas le gaspillage" (I can’t stand waste). Although farmers I met are still in relation with industries in a way or another, they say they would not accept to do everything, “je ne fais pas n’importe quoi » (I don’t do random things).

Thirdly, they think that industrial systems are responsible for malfunctioning world (hunger, climate change, social inequities, deforestation, etc.). For instance, a farmer told me that he doesn’t like that his milk “parte à la laiterie” (lit. goes to dairy industry) and to supermarkets, he feels guilty and responsible for the “agressivité économique” (lit. economic aggressiveness) of these companies. Farmers don’t want to take part in systems that produce a world they don’t like to see. Agro-industries and the farmer union keep telling « vous faites bien » (lit. you do well) « les gens extérieurs n’y connaissent rien » (the rest of society does not know about farming) but « on n’y croit de moins en moins » (we believe less and less in this discourse). “La société nous envoie des signaux” (lit. society sends signals to us); these farmers consider these signals and they want to rethink their ways of farming instead of following the codes, the prescriptions and the rules. In the same vein, they try to be receptive to signals sent by surrounding living nature in order to design alternative farm systems “nous essayons de sentir les besoins de la terre, des bêtes et ils le rendent, un contact s’est rétabli” (lit. we try to feel the needs of the earth, of animals and they give back, there is a contact again).

Finally, industrial projects do not match their own projects and may even undermine them. Agro-industries « ouvrent et ferment comme pour rire » (lit. open and close as for fun), « ils vont nous faire creuver de faim » (they will make us die from hunger), “elles nous laissent tomber” (they let us fall, abandon, or deceive us), so farmers do not trust in industries for long-run projects. New technologies makes “labour that pays back” redundant « dès qu’on ne va plus devoir mettre nos mains dessus (…) on ne va plus rien gagner » (lit. as soon as we won’t have to put our hands on it anymore, (…) we won’t earn anything”). Many of technologies industries offer don’t help them to reach their goals. For instance, the newest machines are neither affordable nor adapted to their needs “ce n’est pas pour nous tout ça” (lit. all this is not for us).

Continuity is threatened

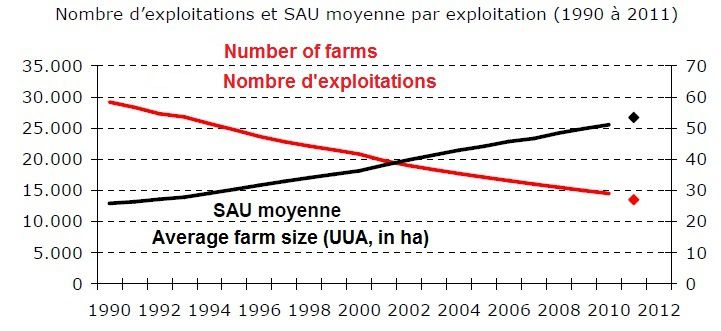

Although most of farmers I met are farming “de père en fils” (lit. from father to son) for decades, the continuity of this activity is not evident and is even threatened. Market forces make farming hard and risky; inputs prices (“les charges”) increase faster than outputs’. Statistical data confirm this “economic squeeze” and shows that many farms are still running thanks to the fact that farmers are not paying wages to themselves (DGARNE - SPW/DGO 3, 2013, p. 61). As farmers cannot do anything about output and input prices, the only way to get an income is to enlarge the farm (reduce labour input per object of labour) and to increase farm “competitiveness” with high-tech and specialized equipment. Then a new problem emerges in farm families: “la reprise” (i.e. when the son/daughter takes over parents’ farm) is really difficult because of too large and specialized investments « ça tue les jeunes » (lit. it kills youth). The young generation gets in debt at a high level and for a long time; it’s often considered as insane « il faut garder une pomme pour sa soif » a farm accountant told me (expr. one should keep something for rainy days)

Thus, the threat comes from outside: “les marchés” (markets), “les factures à payer” (invoices to be paid) threaten their labour income. “Il faut reconnaitre notre travail” (our labour must be acknowledged) “il est grand temps qu’on s’en aperçoive, sinon les jeunes ne vont pas continuer” (it’s really time to be aware of this, otherwise children will not continue). Farmers then warn their surrounding environment that their own disappearance would be damaging. “À côté de nous, on fait vivre le vété, le marchand d’aliments, etc.; on donne du travail” (we make the vet, animal food provider, etc. live besides us; we give them work). If there was only one big farmer per village, there would be « du gros materiel et un chauffeur, et puis c’est tout » (big machines and a driver, that’s all) « ils coupent la branche sur laquelle ils sont assis » (they are cutting the branch they are sat on).

“Les Rapaces”

The threat of “les rapaces” (lit. the raptors or the rapacious) comes from different but entangled processes: scale enlargement, global market competition, farm and region specialization, and CAP premiums. One should keep in mind that this threat is both an issue of land access and land use. “Les rapaces” are taking over land everywhere it is possible to grow commercial crops (wheat, potatoes, beetroots, vegetables for can industry). Rapaces are called by their family name and farmers often talk about them. However, farmers rarely see them as they live further from their fields and they work fast with big machines. Rapaces almost never come to their fields except for intervening (planting, fertilizing, spraying pesticides, and harvesting). They are known for not respecting social norms “les bonnes pratiques entre fermiers” (lit. good practices between farmers) and making non-sustainable use of the land.

Rapaces are either “les gros fermiers du village” (lit. the big farmers of the village) i.e. ‘remaining’ farmers that seek to expand their farms because of the economic squeeze - “la fuite en avant” (lit. headlong evasion) - or “gestionnaires” (lit. managers) of hundreds of hectares who work for large land owners (incl. private companies, local industries, banks). These farms are often mounted in “sociétés” (lit. companies) in order to gather capital (land and machinery -incl. investments made by non-agricultural entities), make the transfer of ownership easier and pay less tax. Their practices are described as immoral; farmers I met experienced them as ruptures towards the social norms that have regulated land access and land use until now.

Attachment to land has a long history in this area, particularly in the “Maugré” stories. For centuries, around Tournai, village communities revenged former tenant who had to leave the land “de mal gré” (i.e. against his will, according to owner’s will) by sabotaging undercover new tenants’ belongings. Indeed, the former tenant would lose the land “enrichie de son travail et de son expérience” (lit. enriched by his work and his skills) (Ravez, 1975, p. 471); village members acted as Robin Hood characters around the contested notion of land ownership. This practice sought to frighten newcomers, prevent rent increases, and witnessed a kind of solidarity among village members against landowners. The last manifestation of “malédiction du Maugré” happened in the late 1970s but it is still one of the major mysterious local stories. Thus, the local custom slowly but hardly disappeared despite repression (public death penalty executions) and new tenure laws.

Today, the law organizes the “bail à ferme” (agricultural usufructuary lease) as the general rule. This frame guarantees land access for at least nine years to the farmer. In this frame, the rent is often cheap and the contract is renewable implicitly - it may even not be written at all. When a farmer retires, there is either “reprise par un enfant” - the right is transferred to the son/daughter - or “remise à un confrère” - i.e. to a colleague. The law also authorizes the “location à l’année” (i.e. rent for a year); this right is negotiable every year and the rent is often much higher. The law foresees that the new tenant gives a certain amount of money to the former for “graisses et fumures” i.e. to pay for investments made by former tenant in field fertility. The law provides the formula to calculate this relatively little amount of money. Besides the legal frame and since the mid-twentieth century, it became socially accepted in this area that in case of “remise”, the new tenant gives “un chapeau” (lit. a hat) i.e. extra money “under the table” -not declared- to the former tenant -in addition to “graisses et fumures”. Since the 1970s, the “chapeau” increased and became the source of many conflicts within and between farm families. Flemish migrants could offer bigger “chapeaux” thanks to the support they got from the Boerenbond; it has happened that fathers chose to sell the farm to Flemish migrants rather than to their own children. Obviously, local farmers find it immoral that newcomers offer “chapeaux” that they cannot afford.

It is said that rapaces take an active part in the “surenchère” (lit. overbid); they are looking for land whatever the price and they offer higher “chapeaux” than what farmers can afford. Thus, they gather land from deactivated farms i.e. when the farmer retires, goes bankrupt or dies, “c’est un monde de rapaces” (lit. it is a world of raptors); farmers say they sometimes lie and bribe to get the pieces of land. Farmers complain that there is no solidarity among farmers anymore; they describe this economic battle for land as “un jeu d’échec” (a chess game) between huge farmers they are not part of nor playing in. Rapaces negotiate short-term tenure agreements with landowners “l’agriculture à contrats” (lit. contracts agriculture). Indeed, under the “bail à ferme”, the land owner cannot increase the rent during the covered period; landowners try not to “tomber dans le bail à ferme” (lit. fall -as in a trap- in the usufructuary lease) i.e. to be stuck for nine years with the same tenant. To do so, they must change of tenant regularly. Rapaces promise to leave the land whenever the landowner wants but demand lower rent than “location à l’année” as a counterpart. Rapaces give a part of the “chapeau” to the land owner also.

Rapaces are also considered as ‘the opposite camp’ in terms of land use; they are ‘entrepreneurs’ « on fait en fonction du marché » (lit. they do according to the market), they are considered as CAP premiums hunters and practice monocrop farming of commercial “speculations" e.g. « blé sur blé » (wheat after wheat). Such short-term calculations are considered as ‘pillaging’ rather than ‘cultivation’. This way of farming is considered as easier and « on serait plus riche » (lit. we would be richer) if ‘we’ did like ‘them’. Most of rapaces do not have livestock so they don’t spread manure « il y a de moins en moins d’éleveurs » (lit. there is less and less livestock farmers). A farmer told me: “je suis trop vieux mais toi tu vas en voir” (lit. I am too old but you will see) “toutes ces sociétés qui cultivent et qui vendent la paille (…) au noir, ils veulent leurs sous” (all these companies that cultivate and sell straw … ‘in black’, they want their money) « ils ne devraient pas » (they should not). As they don’t have manure, he thinks they should at least keep their straw to maintain soil structure. As they manage huge number of fields, they have less time and must work faster « rouler plus vite » (lit. drive -instead of work- faster) with bigger tractors and machines. “La force de frappe des gros, c’est le pulvé” (lit. the core strength of big farmers is their pesticide sprayer). « Ils démolissent plus le terrain » (lit. they destroy more the land) « les tâches sont réalisées n’importe quand » (tasks are done at random moments) « ils ne produisent pas spécialement plus » (they don’t really produce more) « avec l’agriculture par contrats, les rendements stagnent » (in contracts agriculture, yields stagnate) « c’est une dérive point de vue environnemental » (it’s a drifting into environmental degradation) as they cause floodings and soil erosion. Farmers sometimes blame them for starting plowing along the street, not letting grass strips between parcels, spraying herbicides on ditches, removing hedgerows with bulldozers, plowing and draining wetlands & meadows while pocketing subsidies for draining.

As long as the “bail à ferme” runs, farmers are not directly threatened by rapaces; the problem only occurs at the end of the agreement -e.g. when the landowner decides to sell the land- or for farmers who rent “à l’année” -they are in direct competition with rapaces. Thanks to their economic (incl. subsidy) and technological forces, rapaces can buy land more easily and farm fields further in other villages. In some cases, rapaces prevent farmers from getting more land “ce n’est pas evident au village (…) quand on a des gros machins ainsi (…) c’est lui qui a mis le grappin sur tout” (lit. it is not easy in the village … when there are such big [farmers] … he got everything in his grips). When it is possible, farmers try to buy the land they use and avoid letting ‘their land’ go in the hands of rapaces.

Another threat on land are the land use management changes « gens qui décident dans les bureaux » (lit. people who decide in offices) « faudrait leur faire enfiler des bottes » (we should make them put on farm boots). A farm I went to sees its grasslands being converted into housing projects -villas with private gardens. Landowners and real estate companies want to value the constructible land and try to put an end to the tenure agreement. « Il faut toujours se battre » (lit. we always have to fight), as soon as they were done with paying back « la reprise », they had to buy land. « L’avenir est menacé » (lit. future is threatened) « ça nous tracasse » (we are worried about that) “qu’on nous laisse ce dont on a besoin pour vivre!” ([we wish] that they would let us enough land, what we need to live). This last kind of threat involves non-agricultural agents and non-agricultural land use but also provokes a rupture in terms of land use and access regulation -both legal and non-legal. In the same vein, a group of Belgian NGOs is working on the phenomenon of land grabbing and also takes together land use and access changes as threats to peasant agriculture (CNCD-11.11.11; 11.11.11; SOS Faim; Oxfam-Solidarité; Réseau Financement Alternatif; FAIRFIN, 2013).

La carotte et le bâton

Last but not least, farmers are fed up with being ‘subsidized farmers’ i.e. stuck between premiums -the carrot- and conditionality, criteria and controls - the stick. “Tout ce système au dessus de la tête” (lit. all this system upon our head) makes them do an agriculture they did not really chose, and enrolls them in projects of others. Far from being democratic, this system demands farmers’ compliance: to stick to public rules -perceived as changing dreams of politicians- and to industrial standards. « Ces aides, ça te conditionne à beaucoup de choses, se préparer pour les contrôles : la compta, le contrôle bio, la déclaration de la PAC, les MAE… On se mord la queue. Avant les aides, les fermiers étaient trop indomptables. Nous, on est encore indépendants, plus libres mais il faudrait l’être encore plus » (those aids, it conditions you to do a lot of things, get prepared for all these controls: accountancy, organic certification, CAP declaration, agri-environmental measures… We’re biting our own tail. Before the aids, farmers were too indomitable. Us, we are still independent, freer, but we should be even freer). Agriculture modernization brought about the design of institutional systems meant for guiding, piloting virtual units. Thus, the responsibility of system well-functioning -matching with expected outcomes- is located in the ‘rationality’ of the units - they think as they should and adopt the new rationale - and in the design of the system -premiums and criteria induce proper behaviour. In the same vein, some farmers also criticize agricultural schools that kill curiosity « on ne peut pas penser autrement » (lit. one must not think otherwise) and train young farmers to be good and compliant managers.

During the fieldwork, I could feel farmers tiredness of following changing prescriptions, chasing after illusionary and virtual farm functioning. They have the feeling that public rules are aligned with industrial standards and that they will never really fit. They are always ‘special’ and if ever they reach a satisfactory level, it is never the case for a long time. Only the well-equipped specialized farms fit. Although farmers do not agree nor want to comply with all the criteria, ‘the stick’ is always there. “Une nouvelle checklist, ça nous casse les bras” (lit. a new checklist, it breaks our arms); it reaches such a point that farmers sometimes wonder whether these institutions still want them to exist. Farmers blame this institutional apparatus for being exhausting and killing farming attractiveness in the eyes of their children. But Arthur told me: “Nous on va se battre, on ne va pas s’arrêter” (lit. we will fight, we won’t stop) …

Les Indomptables (EN).pdf - Google Drive

https://docs.google.com/file/d/0B8q2goPjcsZSYjFBcjFiRkdLejQ/edit?usp=sharing

Full-text version of the thesis if available via this link

commenter cet article …

/idata%2F4096338%2FCrops-May-2013%2FDSC01090.JPG)

/idata%2F4096338%2FTransition-P.-Temporaire---Cereales%2FDSC00730.JPG)

/idata%2F4096338%2FHersage-des-prairies---Traction-chevaline%2FDSC00266.JPG)

/idata%2F4096338%2FPremiere-parcelle-agroforesterie%2FDSC00228.JPG)

/idata%2F4096338%2F6--Tour-des-cultures---Novembre-2011%2FDSCN1191.JPG)

/idata%2F4096338%2FTour-des-cultures---Octobre-2011%2FDSCN1146.JPG)