Notes de la rencontre avec Jan-Douwe van der Ploeg à Ath, ce mardi 4 novembre 2014.

Profitant de sa venue au Parlement Européen (débat sur l’accaparement des terres en Europe) et au Belgian Agroecology Meeting, nous avons pu organiser cette rencontre avec les agriculteurs du réseau.

Jan-Douwe est professeur de sociologie rurale à Wageningen (Pays-Bas) et Beijing Agricultural University (Chine). Il a consacré sa carrière à l’étude des paysanneries dans de nombreux pays du globe. D’emblée, Marjolein nous fait remarquer que l’écologie du sol et la sociologie rurale sont deux disciplines qui ont disparu des programmes d’enseignement agricole au sortir de la deuxième guerre mondiale.

La redécouverte de l’agriculture paysanne

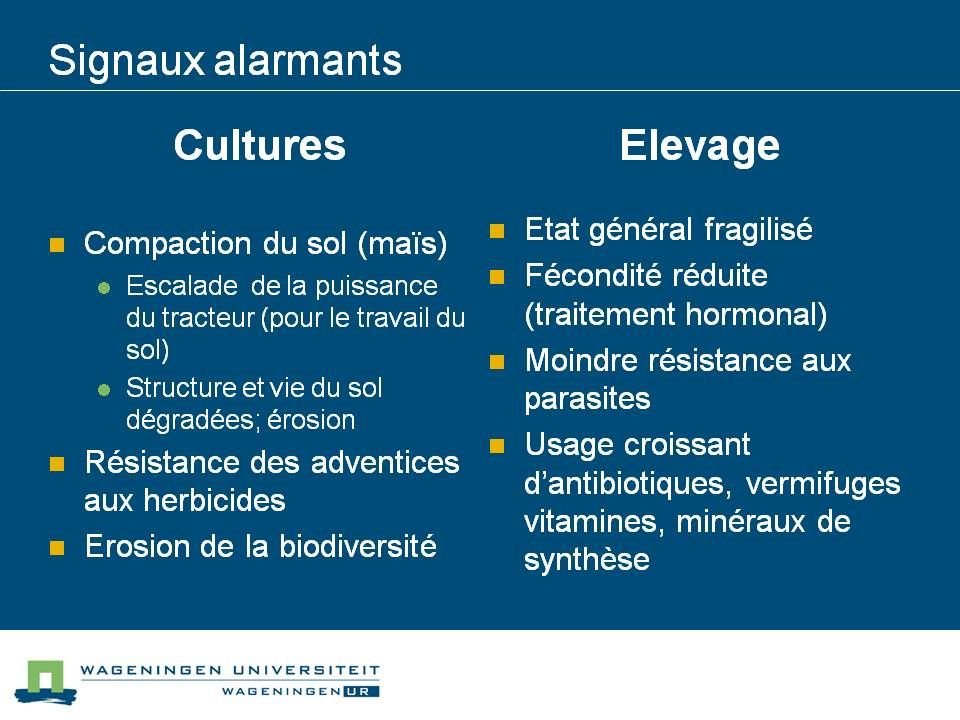

Dans les années 1950 & 60, les revenus dans le secteur agricole ont fortement augmenté grâce à l’accroissement de la productivité. En 1985 environ, une inflexion s’opère : les revenus agricoles commencent à stagner mais les coûts continuent à grimper. A cela s’ajoutent rapidement les systèmes de quotas et les réglementations environnementales. Ainsi, la marge de manœuvre des agriculteurs est fortement réduite ; c’est ce qu’on appelle communément « l’étranglement économique » des fermes (« economic squeeze »).

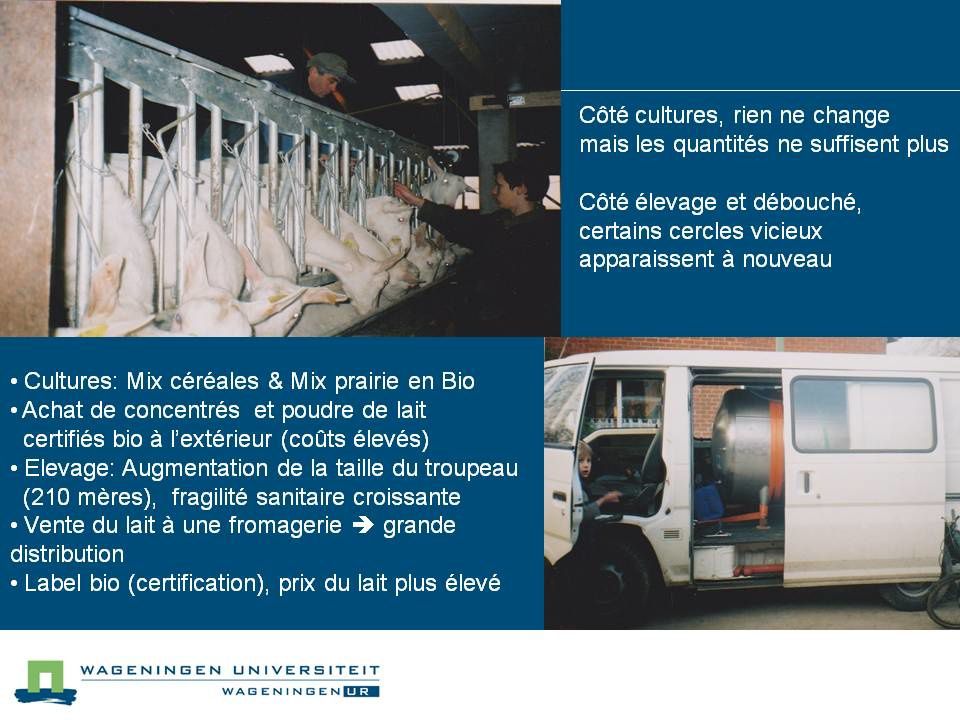

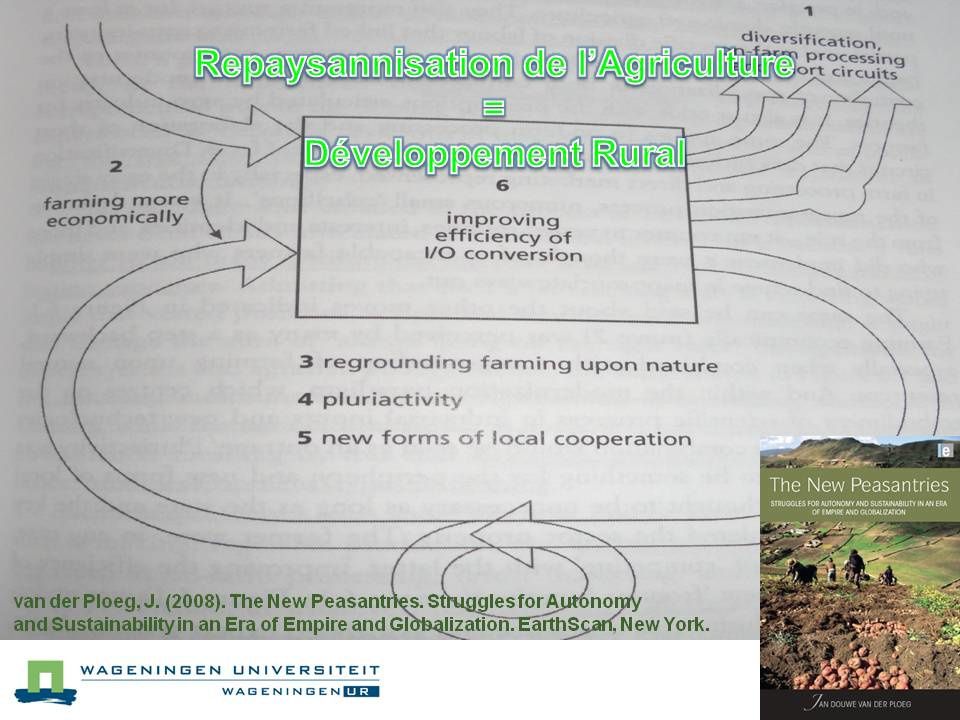

Depuis lors, l’on observe dans les fermes une quête grandissante d’autonomie : les agriculteurs cherchent activement à réduire leurs coûts et à développer les recettes (diversification, production à plus haute valeur ajoutée). Jan-Douwe nous raconte alors plusieurs histoires de fermes qui se font écho. Au Brésil, un mouvement paysan a décidé de « résister et produire » alors que leur activité de production de tomates était menacée par des prix extrêmement bas : ces agriculteurs ont repris la transformation de leurs tomates en main, sur la ferme. Leur slogan est « occuper, résister, coopérer et produire » ; ils ont traduit leur mécontentement en projet vecteur de développement rural. En Italie, plusieurs agriculteurs ont acheté en commun l’équipement nécessaire à la pasteurisation et l’embouteillage du lait. Ils ont monté cet équipement sur un petit camion pour qu’il puisse se déplacer de fermes en fermes. Ils ont ensuite installé des distributeurs de lait pour vendre leurs bouteilles directement aux voisins ; ils ont ainsi « court-circuité » la laiterie et obtenu une meilleure rémunération de leur travail. En Frise (Pays-Bas), des jeunes agriculteurs voyaient leurs activités mises en péril par le classement de leur région comme « réserve naturelle ». Ils ont alors négocié pour prendre en main eux-mêmes la gestion du paysage contre rémunération. Ils ont organisé le compostage de leur fumier afin de réduire leur impact sur l’environnement et ainsi respecter les normes environnementales de manière viable. L’amélioration de la vie du sol a permis de réduire leurs coûts de fertilisation.

Et il pourrait nous raconter des dizaines d’anecdotes similaires. Partout en Europe, de telles initiatives sont prises par les agriculteurs. Ensemble, elles provoquent un véritable « changement souterrain » dans notre agriculture : en termes économiques, elles représentent presque l’équivalent du revenu agricole européen total. Autrement dit, sans elles, l’agriculture en Europe aujourd’hui serait pratiquement impossible. Et malgré cela, beaucoup d’organisations étatiques et scientifiques refusent d’accepter cette réalité ; elles refusent de reconnaitre ces initiatives et leur pertinence à leur juste valeur.

Aujourd’hui, « l’étranglement économique » s’intensifie et se pervertit : la volatilité croissante des prix vient s’ajouter aux difficultés existantes. Du fait de la dérégulation des marchés mondiaux, la fluctuation des prix des produits agricoles est de plus en plus forte. Et le coût des intrants poursuit sa course…

Jan-Douwe nous explique alors la structure de base de l’activité agricole qui peut être définie comme un processus de conversion d’intrants en extrants. Il y a deux moyens d’obtenir les ressources (intrants) nécessaires à ce processus : soit les acheter sur le marché, soit les produire soi-même. De même, les produits peuvent être vendus sur le marché ou consommés sur la ferme. Chaque ferme est donc en équilibre sur deux circuits : le circuit marchand et le circuit non-marchand interne à la ferme. La dominance de l’un ou de l’autre correspond à des modèles culturels différents : le circuit marchand et la « liaison au marché » (« market linkages ») dominent dans l’agriculture « entrepreneuriale », « l’autonomie » et « l’auto-approvisionnement » dominent dans l’agriculture paysanne. Cet équilibre peut varier au fil du temps.

Ensuite, Jan-Douwe nous expose les résultats d’une étude comptable agricole d’une durée de quatre ans (2007-2010) réalisée dans 1200 fermes laitières hollandaises. Cette étude a donc couvert la crise du lait (2008-2009) ; 2007 et 2010 étant considérées comme de « bonnes années » dans le secteur. Cette étude a pris en considération l’historique et l’évolution de ces fermes. Deux catégories distinctes, construites sur l’opposition entre dominance du circuit interne à la ferme et dominance du circuit marchand, ont été nommées respectivement « fermes paysannes » et « fermes entrepreneuriales ». Voici quelques données qui nous ont été présentées.

Premièrement, les deux catégories de fermes se distinguent de façon importante en termes de niveau d’emploi.

|

Nombre d’équivalents temps plein pour produire 1 million de kg de lait (sur une année) |

||

|

|

1987 |

2010 |

|

Fermes paysannes |

3,5 |

3,3 |

|

Fermes entrepreneuriales |

2,5 |

1,9 |

Ensuite, du fait de l’usage plus parcimonieux des concentrés et des fertilisants, les fermes « paysannes » ont montré une efficience de l’utilisation de l’azote plus élevée. Elles peuvent donc être considérées plus « durables ». Comparons finalement leurs revenus.

|

Revenu en 2010 (« bonne année ») |

||

|

|

Cas moyens dans leur catégorie |

Cas « extrêmes » dans leur cat. |

|

Fermes paysannes |

54 000 |

70 000 |

|

Fermes entrepreneuriales |

57 600 |

61 750 |

|

Revenu en 2007 (« mauvaise année ») |

||

|

|

Cas "moyens" dans leur catégorie |

Cas « extrêmes » dans leur catégorie |

|

Fermes paysannes |

32 300 |

69 300 |

|

Fermes entrepreneuriales |

13 170 |

57 350 |

A la suite de ces observations, les chercheurs ont essayé de caractériser les fermes « paysannes », celles qui ont mieux vécu la crise du lait. De l’étude statistique, les caractéristiques ressortent clairement : ces fermes sont celles qui ont un taux d’investissement plus faible (les amortissements et les intérêts pèsent moins dans leur comptabilité), qui produisent moins de lait par unité de travail (plus petite échelle) et qui ont moins de vaches par hectare (vaches davantage nourries à l’herbe).

Beaucoup de personnes ont dit que les paysans allaient disparaître. Dans les faits, de nombreux paysans, partout sur la planète, résistent par leur inventivité et luttent pour davantage d’autonomie. Aujourd’hui, le monde commence à se rendre compte qu’il ne peut se passer des paysans et les défis actuels (chômage, changements climatiques, malnutrition) montrent encore leur raison d’être.

La soirée s’est terminée par un tour de table où Dany, Emmanuel, Elisabeth, Christiane et Francis ont expliqué leurs parcours respectifs, leurs conversions et leurs projets. Jan-Douwe a été très intéressé par la diversité de ces témoignages et les a félicité pour leur persévérance : « vous êtes les pionniers d’un nouveau monde ».

Organisation : Marjolein Visser (ULB), François Serneels (Carah) et Vincent Delobel

RURAL DEVELOPMENT -challenges asn interlinkages - Jan Douwe van der Ploeg - Wageningen The Netherlands

Le site personnel de Jan-Douwe van der Ploeg

/http%3A%2F%2Fwww.agriculturesnetwork.org%2Fpersons%2F70004%2Fperson_photo_thumb)

Les dix qualités de l'agriculture familiale

Même dans le cadre de l'année internationale de l'agriculture familiale, le concept y afférant reste flou : de quoi s'agit-il en fait ? Qu'est-ce qui en constitue la caractéristique singulière...

Article écrit par Jan-Douwe, traduit en français.

commenter cet article …

/http%3A%2F%2Fwww.agroecologie.be%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2014%2F06%2FBAM2014-vignette_150ppp.jpg)

/image%2F0670498%2F20140915%2Fob_dfb509_img-0863.JPG)

/image%2F0670498%2F20140915%2Fob_8f2ef6_img-0871.JPG)

/image%2F0670498%2F20140915%2Fob_7e4df7_img-0879.JPG)

/image%2F0670498%2F20140915%2Fob_432c8b_img-0888.JPG)

/image%2F0670498%2F20140915%2Fob_0851fc_img-0896.JPG)

/image%2F0670498%2F20140425%2Fob_59121d_dsc-3839.JPG)

/image%2F0670498%2F20140425%2Fob_18cc69_dsc-3841.JPG)

/image%2F0670498%2F20140425%2Fob_76832c_dsc-3842.JPG)

/image%2F0670498%2F20140425%2Fob_f6be4d_dsc-3844.JPG)

/image%2F0670498%2F20140324%2Fob_c915bf_dsc01800-copie.JPG)

/idata%2F4096338%2FCrops-May-2013%2FDSC01090.JPG)

/idata%2F4096338%2FTransition-P.-Temporaire---Cereales%2FDSC00730.JPG)

/idata%2F4096338%2FHersage-des-prairies---Traction-chevaline%2FDSC00266.JPG)

/idata%2F4096338%2FPremiere-parcelle-agroforesterie%2FDSC00228.JPG)

/idata%2F4096338%2F6--Tour-des-cultures---Novembre-2011%2FDSCN1191.JPG)

/idata%2F4096338%2FTour-des-cultures---Octobre-2011%2FDSCN1146.JPG)